In a world awash in questionable information, libraries are commonly trusted sources. We need to honor, preserve, and protect that trust—and to be aware of the people who haven’t found trust in us yet. There are useful lessons to learn from a profession that’s seriously examining its own trust factors: journalism.

This is part two of a series. Part one is here.

People tend to trust libraries.

People tend to trust libraries.

Multiple studies by Pew Research as well as studies by the Maine State Library and CILIP, the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals, confirm the trusted status of librarians. When it comes to sources the public looks to with confidence, we sit near the top of the list, shoulder to shoulder with health care providers and significant percentage points above news organizations, government agents, and social media. Relatively speaking, libraries and librarians are known as credible sources, relied on by those looking for information that will make a difference in their lives.

Journalists are another story.

Our “information-gathering cousins” (David Beard’s coinage) have been grappling with serious questions of public confidence. As consumers negotiate the uneven landscape of “the media,” picking their way through a confusion of “fake news,” they aren’t always clear about how the news is generated, who is generating it, or whether it’s even real.

“I was a journalist before I came to the Pew Research Center, and it has been enlightening to me during our research to see how many points of similarity the worlds of libraries and news organizations have,” notes Lee Rainie, director of Pew’s internet, society, and technology research, in an interview. “At the same time, these institutions have different missions, and I think journalists are focused on reporting on public and civic life in a way that is very different and somewhat more controversial from the way libraries try to serve their communities.

“It doesn’t help that the news environment has become so balkanized and polarized, often without news organizations changing their practices. Audiences for news have changed in the internet era. That doesn’t seem to be the story in library patronage. Libraries aren’t deemed to be partisan institutions in the public imagination.”

So why should libraries think about journalism when it comes to questions of public trust? Because professional reporters practicing evidence-based journalism want their work to matter. They’ve been putting significant time and energy into studying the information environment, their communities, and their own practices, looking for ways to build confidence in their work.

While public trust is essential for libraries, we have not been studying the nature of trust the same way. As we work to preserve the trust we’ve earned and to build trust among those who are wariest of their sources and institutions, there are things we can learn from the journalism research: The significance of being local. The need to listen carefully. The importance of working transparently. The value of knowing and living up to our standards.

These things matter.

Local matters

Local matters

When it comes to trust, it’s important to be perceived as part of the local community.

“Study after study after study has shown that as trust has plummeted across many parts of the media, local news has consistently been rated as more trusted,” explains Josh Stearns, director of Democracy Fund’s Public Square Program. “There are many reasons for this, including: Local news is viewed as more proximate, more relevant, more accountable, and more motivated by a shared sense of concern for the community. Local journalists are our neighbors. Indeed, the work of the Trust Project includes localism and local sourcing as one of eight core indicators of trust.”

Our communities are where we live and what we know, so it would seem natural for people to support and embrace their neighborhood institutions. When Pew Research looked at citizen engagement with libraries, researchers found that “the people who are most avid library fans are also quite civically minded [and] usually have great fondness for their communities and local institutions,” notes Lee Rainie.

How to build on that base of civic support could be a topic for brown bag lunches and strategic planning conversations. We can foster public trust as we strengthen local connections, stay visible, and make sure residents and leaders know what we’re doing for the people in our service areas. But to become fully embedded in a community, a library needs to be more than a service institution: it needs to be formed of the community itself. People need to feel, as Stearns says of local news, like the library is “not just something that happens around them or to them, but happens for them and with them.“ People need to be part of the programs, part of the collection, part of the planning process, part of the library.

“Local” matters, but this isn’t just a label or a location. It’s a mindset, among librarians and the public, that recognizes the library as an essential element of the environment, a community resource that’s locally sourced, locally grown, locally sustained.

Listening matters

Listening matters

If a community’s information ecosystem is to stay healthy, the community’s members need to have a voice. For trust to grow, we need to listen.

“Building loyalty and trust requires tuning into the concerns and voices of the whole community,” writes journalist Andrew Haeg, CEO of GroundSource. Listening to and engaging people, imagines Haeg, will “help news outlets speak as a genuine proxy for the community—left, right and center—at a time when people need more than ever a voice they can trust—that feels like it’s theirs, really.”

Journalists are taking audiences seriously and looking for ways to listen. The American Press Institute, the Listening Post Collective, Gather, and others are creating guides and resources for listening to audiences. The News Integrity Initiative has declared 2018 “The Year of Listening,” and a spate of new organizations and tools are helping reporters turn their work into two-way exchanges. Mobile apps from GroundSource, for example, let journalists “tap in and be more responsive to the conversations happening around you.” Software from Hearken (which literally means “listen”) encourages “public-powered journalism” by drawing audiences into the reporting process from the very beginning, when story ideas are generated. Open source tools from The Coral Project help to bring “journalists and the communities they serve closer together.” (These tools, by the way, can have applications in creative libraries. Check ‘em out.)

“We do this,” says The Coral Project, “to raise public trust in journalism, to increase the diversity of voices and experiences reflected in news reporting, and to improve journalism by making it more relevant to people’s lives. Because journalism needs everyone.”

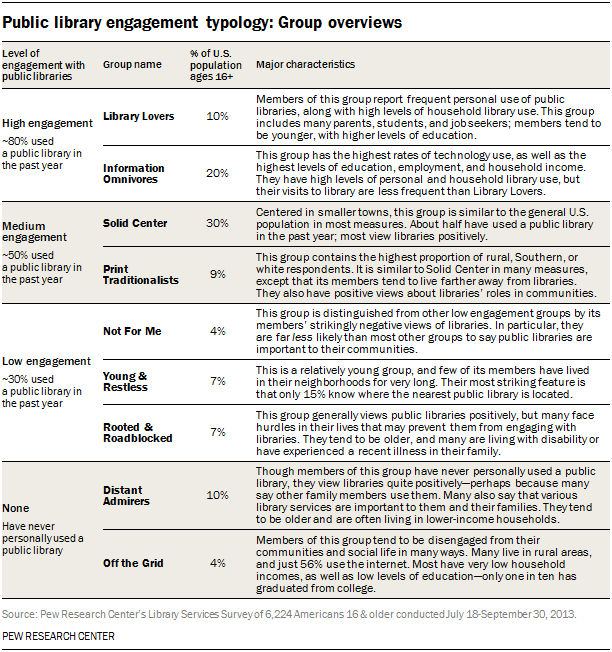

Libraries need everyone too, and we need to hear the people who don’t use or trust libraries, as well as those who do. Thanks to Pew Research, we have a pretty good idea of who is and isn’t engaged with libraries, from the “library lovers” to those who are “off the grid.” Pew’s look at the spectrum of public library engagement and Lee Rainie’s analysis of where libraries fit into the information needs of citizens can give us frameworks for thinking about where we need to reach community subgroups and reinforce trust.

Where to focus is the next question. Do we reach out those who are barely engaged? Or could there be more opportunities to have an impact with folks in the middle, who may have more positive associations with libraries? The answers may be different in different communities. “One thing that’s clear from our data,” says Rainie, “is that library lovers are willing to help librarians answer this question. They’ll give feedback on ideas that libraries are pursuing to build their user base. They will network and advocate on behalf of libraries. It’s a resource that goes untapped by lots of the libraries to which I speak.”

All we need to do is ask. And then listen.

Transparency matters

Transparency matters

Listening helps us hear those outside of our circles. Transparency invites them inside. When it comes to trust, it’s important to let people see inside the organization, exposing parts of our work we may not be used to sharing.

Sometimes people really do want to know how the sausage is made. They want to know the ingredients, understand the process, see the evidence. This is not a new concept—the American Press Institute reported on “the best ways for publishers to build credibility through transparency” in 2014—but it’s more important than ever now. “The transparency movement has finally come of age,” says Jay Rosen, associate professor of journalism at New York University.

When “transparency becomes the primary means of trust production,” as Rosen says, we need to understand clearly what transparency means. Beyond the basic expectation to cite sources and credit authors, according to Rosen, it means showing your work, so people understand how the results came to be and what influenced them. It calls for openness about where you’re coming from, so people know what lens they’re seeing through. It means sharing your priorities and agendas. Disclosing what it costs to do the work, and inviting the public into the process. “These are the new terms on which trust can be won in journalism,” says Rosen. There’s more, and there’s plenty that applies to libraries.

Librarians are clearly committed to citing sources, one of the key trust indicators identified by the Trust Project. Can we do more? Can we find ways to be more up front about how and why we do what we do? Can we be more open about how we set priorities and make decisions, about what it costs to serve our communities? There may be ways we can show more of our work, reveal our thinking, and publicly correct our mistakes.

Not everyone will want to look behind the scenes at the library. But trust may be earned when people feel you have nothing to hide.

Standards matter

Standards matter

Ethics and values also matter. It’s important to know what you stand for, to make your principles known and then stand by those principles.

“People trust an institution because it seems to have an ethic that makes those within it more trustworthy,” writes Yuval Levin in American Journalism as an Institution, part of a white paper series on media and democracy commissioned by the Knight Foundation. For journalists, “The value of certain formal, institutional structures—a code of conduct taken seriously, an overt professionalism, a system of vetting and fact-checking, a newsroom, an editorial team—should not be underestimated.”

A respected code of conduct. Demonstrated professionalism. A system of vetting and fact-checking—in library language, curating and authenticating. We can check those boxes. All staffers need to be aware of how important those professional practices are, and we need to make them visible to the public.

The Society of Professional Journalists details a code of ethics, and some newsrooms have taken things a step further, publicly defining what they stand for in their communities. Working from the premise that “Journalism is best when pursued with purpose,” the Voice of San Diego staff and board defined shared values and concerns that include things like “a well-informed, well-educated community ready to participate in civic affairs” and “high-quality education for all children.”

“We stand for certain things in the community,” Voice of San Diego editor-in-chief Scott Lewis told Neiman Lab reporter Laura Hazard Owen, and articulating those things helped clarify both their own work practices and the public’s understanding of their work. “When someone asks: What is your agenda? We can say this is our agenda,” says Lewis. “When someone asks: What is your bias? We can say this is our bias… and then we can be impartial about the solutions, nonpartisan about the way they are addressed.” (This is an interesting view to consider in the ongoing discussions of library neutrality, by the way.)

In addition to the ALA Code of Ethics or other national code, does your library have a statement of values, or something that documents what you stand for in the community? Does it guide your decision-making and your day-to-day work? Is it visible to the public on your website and in your building? (See also: Transparency Matters.)

Trust matters

Trust matters, especially for those who serve as public resources for information, learning, and community building. Yes, libraries already have relatively high trust levels, and that trust is extraordinarily valuable when our whole information ecosystem is under stress. But sustaining public confidence takes effort, and we still have opportunities to grow trust in the more skeptical patches of our communities.

Journalists are learning from our experiences. Let’s see what we can learn from theirs. Ω

Resources

Note: These are selected research reports and collections of toolkits and guides. There are many more useful resources linked within the post above, and in part 1 of this series.

American Journalism as an Institution, by Yuval Levin for the Knight Foundation. 2018.

“The best ways for publishers to build credibility through transparency,” by Craig Silverman for the American Press Institute. September 24, 2014.

“Resources for listening to audiences,” from the American Press Institute. 2018.

“What is a trust indicator?” from the Trust Project. 2017.

Illustrations by Kerry Conboy.

As librarians work to build and preserve trust, there are things we can learn from the journalism research:

The significance of being local.

The need to listen carefully.

The importance of working transparently.

The value of knowing and living up to our standards.

People need to feel, as Josh Stearns says of local news, like the library is “not just something that happens around them or to them, but happens for them and with them.“

“Building loyalty and trust requires tuning into the concerns and voices of the whole community.”

—Andrew Haeg

When “transparency becomes the primary means of trust production,” as Jay Rosen says, we need to understand clearly what transparency means.

“People trust an institution because it seems to have an ethic that makes those within it more trustworthy.”

—Yuval Levin